Just Toilets

Visitors from the past would find modern life practically unrecognisable. From takeaway lattes to TikTok, our contemporary traditions are almost nothing like those of our ancestors. Except when we’re caught short.

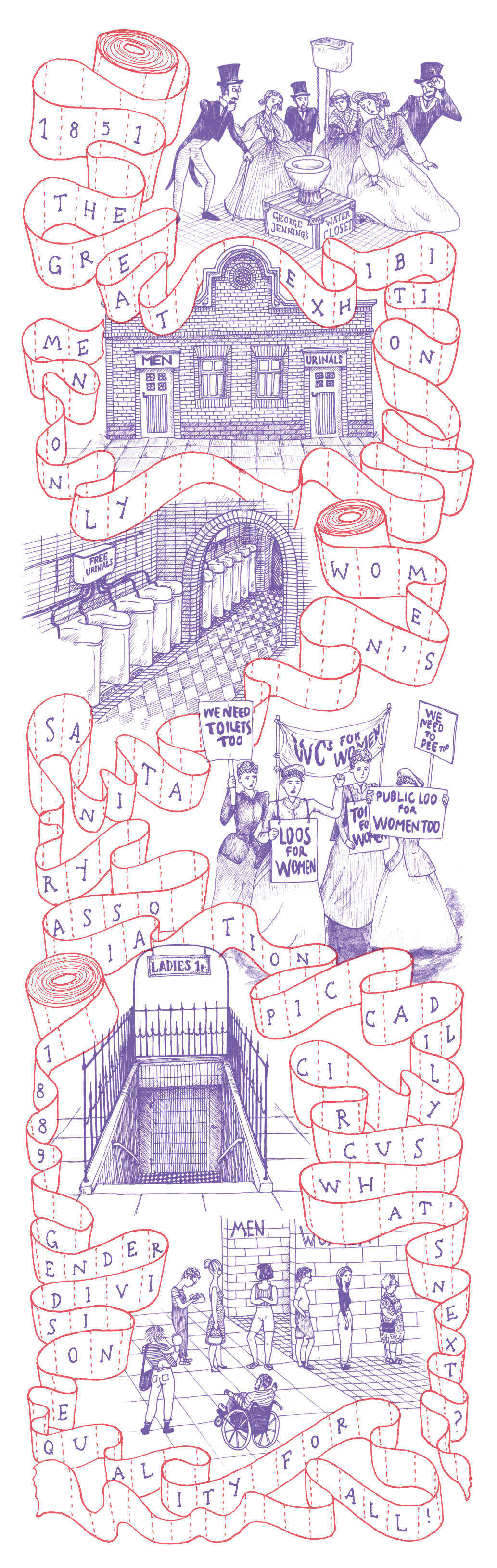

The first British public toilets were built below Victorian London’s streets in the mid-19th century. Their construction, necessitated by rapid urbanisation and industrialisation, was made possible by the invention of mass-manufactured water closets, first exhibited by George Jennings in the 1851 Great Exhibition. Today, the design of many contemporary public loos across the world still reflects the Dickensian values, ideas of proprietary and attitudes to gender that were built into those early experiments in public sanitation over 150 years ago.

Initially, British public toilets were only for men. According to social norms of Victorian society, femininity was something modest; best concealed and protected. Women were expected to look after the home, not wander the city by themselves. The idea of public ladies’ rooms was unthinkable. As is the case with many bastions of social progress, women’s toilets were fought for by activists and campaigners, such as the Ladies’ Sanitary Association who demanded facilities for women in 1878, finally seeing their demands met with the opening of ladies’ toilets in Piccadilly Circus eleven years later.

Progress in the provision for women was slow and failed to include users of lower social classes. Whilst men’s urinals were free, ladies’ WCs incurred a charge, effectively excluding working class women from using them. Even today, many of London’s public loos are not free to pee, with Network Rail, the owner of many of London’s greatest train stations, only pledging to phase out charges on toilets in 2019.

In her book Invisible Women, Caroline Criado-Perez, acknowledges the gendered issues of toilets in London but also highlights the graver problems women around the world are faced with when deprived of adequate sanitation. In some regions of India, for example, insufficient provision of toilets means women have to restrict fluid intake during the day and wait to relieve themselves after dark, which, in addition to severe health risks, increases the threat of sexual violence and rape. The Right to Pee campaign advocates for the construction of more ladies’ facilities across Mumbai as currently only one-third of the city’s public toilets are for women.

Inadequate provision of public toilets – whether in number of units or by design – impacts not only women but also other marginalised societal groups. Historically, restricting access to sanitation has been used to segregate people by gender, class, disability and race. Today, the transgender community is at the forefront of the fight for dignified toilet provision but it is worth remembering that the range of people who require better public restrooms to fully participate in public life is much wider. Menstruating or pregnant people, the elderly, parents with small children, people with disabilities and invisible medical conditions all rely on free access to lavatories in order to move comfortably around the city.

Increasing the number of publicly-accessible facilities is an essential step in the quest for just toilets, but the difficulties faced by transgender people also highlight the fact that traditional gender-segregated public lavatory design needs critical revision. Some toilet operators now provide a unisex cubicle alongside traditional men’s and ladies’ rooms, often doubling as an accessible loo for less mobile users. But this band-aid approach only further stigmatises those who don’t comply with Victorian gender identities and people with disabilities.

Today’s public toilets are also increasingly less public and are often being replaced by ‘publicly accessible’ but privately owned facilities located in commercial establishments such as shopping centres and cafes. Often users must be paying customers, or look like potential ones, to be allowed access raising further ethical questions. Outside the malls and restaurants, pre-assembled cubicles are now regularly fabricated with a host of dehumanising hostile design features intended to discourage vandalism and anti-social behaviour: doors which open automatically after ten minutes; glaring blue lights which make it hard to find veins; low cubicle doors that allow security guards to surveil toilet users.

Although still too rare, a more respectful approach to inclusive toilet design comprising individual gender-free rooms, either with integrated or shared washing facilities, can increasingly be seen in new buildings. American architect and Yale professor, Joel Sanders goes further, arguing that care and attention need to be focused not only on biological requirements, but also psychological needs such as religious traditions. In Sanders’ project ‘Stalled’, public toilets are creatively reimagined as accessible, sustainable and playful landscapes with different zones dedicated to eliminating, grooming and washing. Besides toilets, Sanders’ prototype features remediating planters, a trough for Muslim people to perform ritual ablutions and curtained alcoves for breastfeeding, administering medication or private prayer. Sanders’ proposals reject the binary gender divide in loos and instead respects considerations such as age, disabilities, religion, psychology and social structure to propose a solution that, he argues, ‘meets the goals of social equity, diversity, and inclusion.’

For the privileged few public toilets are often taken for granted, but their role in controlling who is able to fully participate in public life and who is overlooked has been, and still is, profound. A radical rethinking of this utilitarian piece of architectural infrastructure can not only bring about wider inclusivity within the urban realm but also greater creativity. Better toilets for women and the marginalised mean better cities for everyone.

Marianna Janowicz